Babylon and the First Astronomers

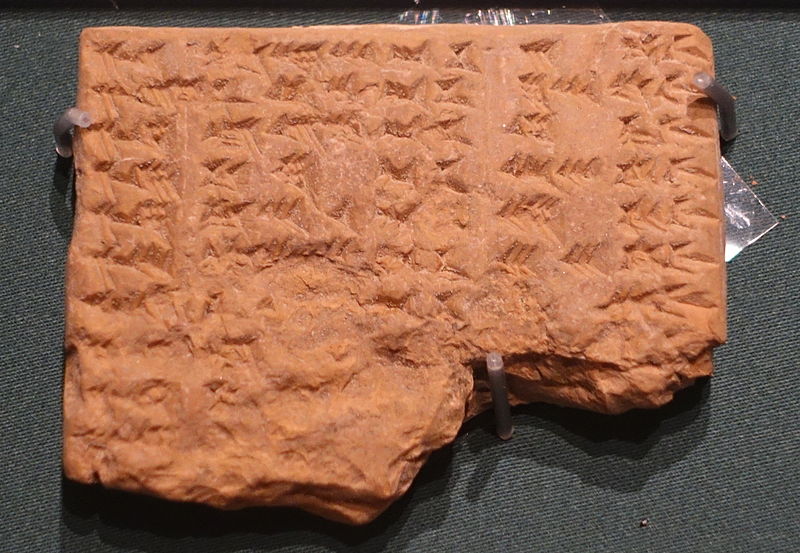

The Babylonians , near modern Baghdad, recorded their observations of the sky in clay tablets, most of which would fit in the palm of your hand, using a kind of shorthand. I’ve listed this at 900 B.C. on our timeline, but some authors place the date of the first recordings at close to 1400 B.C. Others claim the Babylonians recorded their geometric analysis of the planetary movements in their astronomical tablets.

The tablet pictured here is said to record observations of the consecutive reappearances of Venus as

the evening star for 24 years. Regardless of the dates, the Babylonian records made their way to

Greece probably as a result of Alexander the Great’s conquest. According to a Greek historian – Simplicius,

whose name shows up again in

Galileo's

story – Alexander ordered his chronicler to translate the

records, who in turn sent them to his uncle –

Aristotle.

These extensive records are almost certainly the source material

for Aristotle’s model of the cosmos.

The tablet pictured here is said to record observations of the consecutive reappearances of Venus as

the evening star for 24 years. Regardless of the dates, the Babylonian records made their way to

Greece probably as a result of Alexander the Great’s conquest. According to a Greek historian – Simplicius,

whose name shows up again in

Galileo's

story – Alexander ordered his chronicler to translate the

records, who in turn sent them to his uncle –

Aristotle.

These extensive records are almost certainly the source material

for Aristotle’s model of the cosmos.

The tremendous contribution of the earliest civilizations in Mesopotamia is amazing for what it tells us about human interest in the stars, but I think even more interesting for another reason.

As much as 1000 years passed after these early days of organized astronomy before any coherent theory of the cosmos was developed – at least one that survives for us to examine. The more advanced the Babylonian conception of the cosmos, the more puzzling the 1000 years of little or no progress seems to be. Why does human discovery seem to move in fits and starts? How is it that huge steps backward happen after truth is first discovered? If knowledge of these things were lost to civilization – then rediscovered – what else might have once been discovered and then NOT rediscovered?

We generally assume a steady and accelerating rate of human discovery and invention, especially in our present period of history where the change over a single lifetime is almost unimaginable. But that is not the lesson of history. In the past, periods of rapid progress have come to an end. The accomplishments of a civilization are lost to future generations with perhaps only fragments recovered at a later date.

What does this tell us about our possible futures?