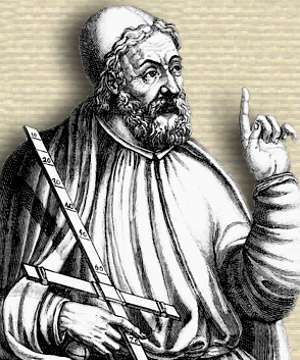

Ptolemy Moves the Earth Off-Center

Although Aristotle's model captured the minds of astronomers and lay persons alike for a thousand years, Ptolemy made it work. Probably working in the Egyptian city of Alexandria most of his adult life, Ptolemy made his proposal in a book called “Almagest” (or The Great Compilation) published about A.D. 145. To make Aristotle’s model work, Ptolemy had to move the Earth from the center of the Universe to a point offset from the center. He also had to abandon the steady motion of the planets around their orbits, instead having them move in their circular orbits at a variable speed which made them appear to move steadily around an imaginary “equant point” offset from the center of the Universe opposite from the Earth.

Ptolemy was forced to abandon many of the fundamental principles of Aristotle’s model in order to

save it from its apparent failures. The one concept Ptolemy did not abandon was the idea of an

interconnected system of perfect spheres. In fact, Ptolemy’s model was careful to avoid any overlap

of the epicycle spheres, presumably to maintain the reasonableness of these sphere’s as actual

physical realities.

Ptolemy was forced to abandon many of the fundamental principles of Aristotle’s model in order to

save it from its apparent failures. The one concept Ptolemy did not abandon was the idea of an

interconnected system of perfect spheres. In fact, Ptolemy’s model was careful to avoid any overlap

of the epicycle spheres, presumably to maintain the reasonableness of these sphere’s as actual

physical realities.

Almagest and Ptolemy’s many other works were highly regarded by astronomers from antiquity through the Renaissance for their predictive power, ease of computation and clarity, but the soul of astronomy for most practitioners (probably including Ptolemy himself) remained Aristotle. There is hardly a better example of the power of an idea to overwhelm data, reason and logic once it has become firmly established.

Like all of the other key developments in astronomy (and science in general, for that matter), we give Ptolemy credit for a host of new ideas because he pulled together the innovations of others, added his own key ingredients, and most of all because he expressed his conclusions in a way that others could appreciate. Our idea of science as a series of dramatic events that can be laid out on a timeline like this one is a useful one because it helps us see the evolution of modern notions from less modern ones. But this view masks the true nature of the evolution of knowledge – which is chaotic, prone to firmly held and persistent errors, rife with the worst kind of politics, and much more driven by a constant interaction of smaller (often incorrect) ideas that slowly congeal into a set of better notions vs. isolated flashes of insight that comes as a bolt from the blue.

The popular notion today is that the dogma of formal religions was the great impediment to advancement of scientific thought. But the persistence of Aristotle’s spheres despite contrary evidence is hard to blame on religious thought – surviving as it did through age after age of human history. Instead, I think this story illustrates much more fundamental human tendencies, both in habits of thought and political influences.